The San Felipe Trail

Most Houstonians associate the stretch of San Felipe between River Oaks and the Memorial area with the ritzy mansions, restaurants and shopping centers that line this prosperous thoroughfare often used as an alternate east-west route when traffic clogs Westheimer and Interstate 10.

What many Houstonians don’t realize, however, is that the full extent of the path taken by this street represents one of the earliest thoroughfares that connected the state’s most famous colony — San Felipe de Austin, near present-day Sealy — and the port city of Harrisburg (precursor to the city of Houston), just east of present-day downtown on the banks of Buffalo Bayou.

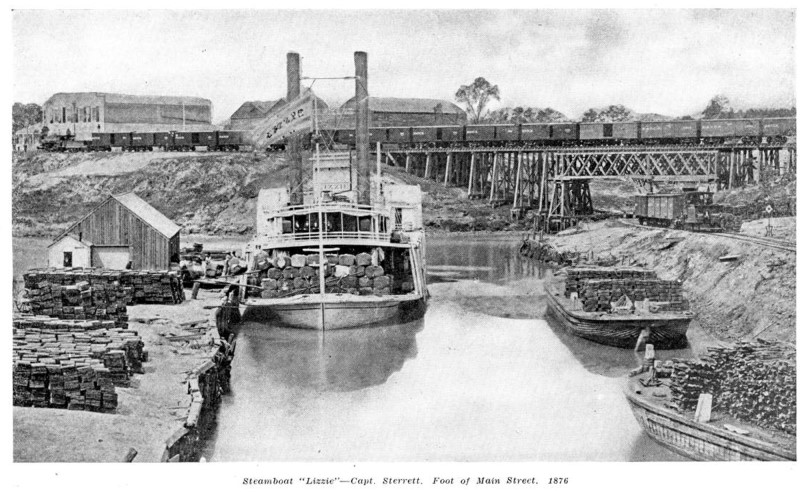

Buffalo Bayou 1878

Buffalo Bayou 1878

The Portal to Texas History

The San Felipe Trail, as it was called, generally followed the south bank of Buffalo Bayou and acted as a trade route between the cotton plantations along the Brazos and Colorado rivers near the Austin colony and the improvised ports along Buffalo Bayou at Houston and Harrisburg. Riverboats would then take cotton and other materials to the port of Galveston for shipping nationally and internationally.

When the riverboats steamed back to Houston, they were often carrying immigrants from Germany. The Germans headed west on the trail, famously settling in Central Texas and establishing towns such as New Braunfels and Fredericksburg.

The eastern movement of cotton and the westward migration of German immigrants along the San Felipe Trail would eventually lay the foundation for the two predominant styles of Texas barbecue — the Central Texas style that developed around Austin and Southeast Texas style that developed in Houston and points east to the Louisiana border.

In antebellum Texas, the cotton plantations along the Brazos and Colorado were worked by African slaves brought there by landowners from states such as Mississippi and Alabama. After the end of the Civil War and the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation (and the “Juneteenth” order in Galveston of June 19th, 1865), former slaves traveled east along the San Felipe Trail, settling just outside downtown Houston, along the stretch of the trail which is now West Dallas Street.

This area, known as Freedmen’s Town, became the center of Houston’s African-American community starting in the late 1800s. It also became the center of Houston’s own tradition of Southeast Texas-style barbecue that combined Southern U.S. cooking traditions brought here by slaves, as well as Cajun and Creole techniques brought here from Louisiana.

By the early 1900s, Houston was booming and restaurants were opening at a rapid pace, including many barbecue stands. The 1912 and 1913 city directories listed 15 barbecue stands, with six of them in Freedmen’s Town (also known as Fourth Ward) and four in Fifth Ward, where African Americans of Creole origin settled. All 10 of these were owned by African Americans. The remaining five were downtown and owned by white proprietors.

A typical Fourth Ward barbecue joint of the time was at 709 San Felipe, now a parking lot at the corner of West Dallas and Interstate 45. The proprietor is listed as Lavinia Camper, a widowed African-American woman born in Mississippi in the 1860s.

There’s no way to know what was served at Mrs. Camper’s barbecue stand. But later barbecue joints in the Third, Fourth and Fifth wards reflected the mostly pork-based, sauced barbecue that would become the foundation for Southeast Texas-style barbecue.

It’s not a stretch to imagine that as former slaves traveled east along the San Felipe Trail, they passed bands of German immigrants heading west. These Germans, along with Czech immigrants, would become known for establishing meat markets in Central Texas, where they applied their knowledge of cooking and smoking to the plentiful beef of the area, creating the style of barbecue for which that region is known.

Today, driving past the H-E-Bs, Whataburgers and Starbucks along San Felipe, it’s hard to envision this was one of the most important thoroughfares in the history of Texas and Houston, and the barbecue traditions that would eventually flow from it.