Houston's Connection to Central Texas Barbecue

In 1911, the intersection of Travis and Preston in downtown Houston thrummed with activity. On the northwest corner, the City Hall and Market building hosted a cornucopia of oyster stalls, fruit and vegetable stands and butcher shops.

The block of buildings on the southwest corner reflected what would become the melting pot of immigrants, entrepreneurs and wildcatters that Houston is known for to this day.

An office building on the block housed a collection of African-American professional offices — doctors, dentists, attorneys and Realtors. The J.M. Geiselman meat market occupied a ground-floor space. One of Houston’s oldest family dynasties also got its start here: The Guseman Shoe Repairing Co., at 408 Travis, became the foundation for a fortune made from downtown real estate, overseen by patriarch Tanny Charles Guseman and culminating in the construction of the Auditorium Hotel (now Lancaster Hotel). A Japanese restaurant (“Okasaki”), Greek diner and saddle shop all played a part in the block’s rich diversity.

And right on the southwest corner, facing Market Square, was Otto’s Bar, helmed by German émigré Hugo Prove. He lived at 2103 State in Sixth Ward with his wife, Amelia, née Kreuz.

German immigrants began arriving in Galveston in the early 1800s and took riverboats along Buffalo Bayou to Houston, where they disembarked. Some stayed in Houston — Mitchell Louis Westheimer being the most prominent — while many others kept traveling west to Central Texas to establish cities including Fredericksburg and New Braunfels.

Not much is known of Otto’s Bar, other than from police reports of the time. In the Sept. 17, 1909, edition of the Houston Chronicle, an altercation at the bar was reported in which one J.A. Fisher was “stabbed about the arms” by Ollie Dubard. Though “an artery was cut and he almost bled to death,” Fisher “revived sufficiently to walk to his home.”

Such were the circumstances of Houston’s Market Square in 1911. Though the exact reasons are lost to history, Hugo Prove decided a change of scenery was in order for him and Amelia. A notice from the Feb. 25, 1912, edition of the Chronicle announced that “Hugo Prove of Houston has purchased an interest in the Kreuz Bros. meat establishment” in Lockhart.

ca. 1900

ca. 1900

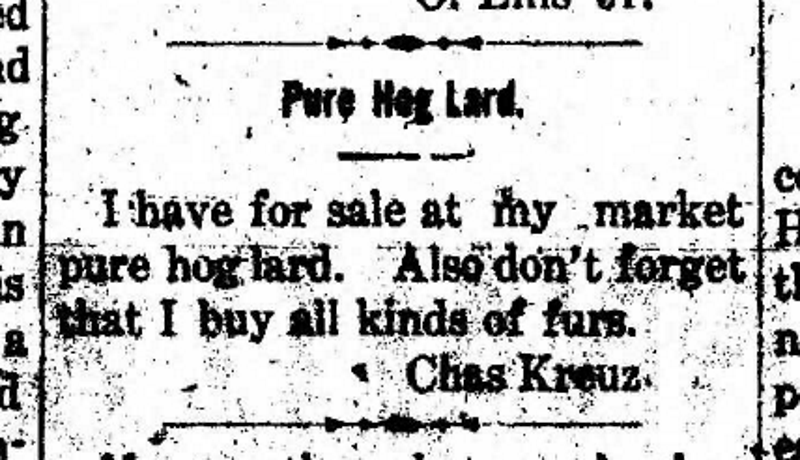

Indeed, Amelia was the daughter of one of the forefathers of Central Texas-style barbecue, Charles Kreuz Sr., who opened Kreuz Market in Lockhart in 1900. To this day, Kreuz Market as well as its sister restaurant Smitty’s Market continue as the standard-bearers for this meat-market style of barbecue.

Charles was born in Seguin in 1855 to German immigrants Florenz and Sophie Kreuz. He moved to Lockhart in 1900 and purchased the first meat market in the city, established in 1875 by Jesse Swearingen. In 1911, Kreuz sold the business to his sons Theodore, Will and Alvin. Will eventually sold his share to sister Amelia and brother-in-law Hugo in 1912.

By all accounts, Hugo played a central role in the business. His obituary noted that “he did his part in establishing the company.” A mention in the Lockhart Post-Register from Jan. 29, 1931, noted that “At the Kreuz Market there was displayed for sale an unusually fine cabbage which was grown by Hugo Prove.

Eventually the Kreuz family would jettison the grocery aspect of the business and just sell barbecue. Because of a well-known family feud, the “Kreuz Market” name was moved to a newer building on the outskirts of town, but the original Kreuz Market established by Charles senior and his family still exists, now named Smitty’s Market.

The original building still has the all-brick, in-ground barbecue pits, as well as soot-darkened iron rails along the ceiling used to move beef carcasses around when the building was a working meat market. A narrow hallway features plank-wood tables, still draped with the chains that many years ago were attached to communal knives that patrons used to cut their meat. The chains were there to prevent customers from stealing them.

Or so the story goes. Legend has it that the chains were actually needed so rowdy patrons wouldn’t use the knives on each other during an altercation. Perhaps those chains were Hugo’s most important contribution to Kreuz Market and the tradition of Central Texas barbecue, a reminder of his wild and wooly days at Otto’s Bar in Houston’s Market Square.